Coffee Varieties Conservation Project at the Wilhema Botanical Garden

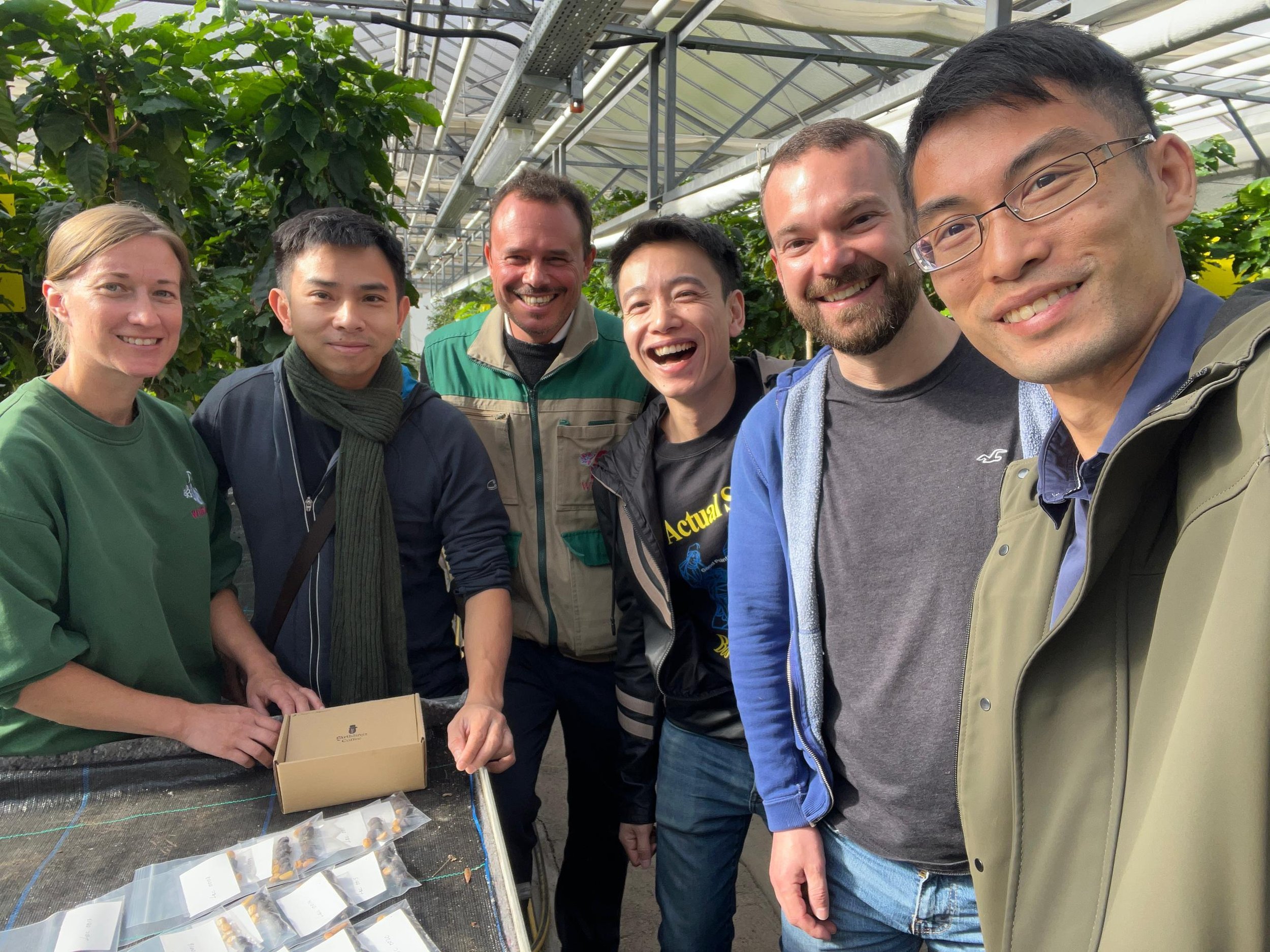

We’ve finally completed the latest round of seed exchange with the Wilhema Botanical Garden, Stuttgart, Germany. Time flies, our collaboration on the Coffee Varieties Conservation Project has been ongoing for almost 6 years. This marks our third visit, and it's the one where we've brought the most samples (20 suspected Liberica variants).

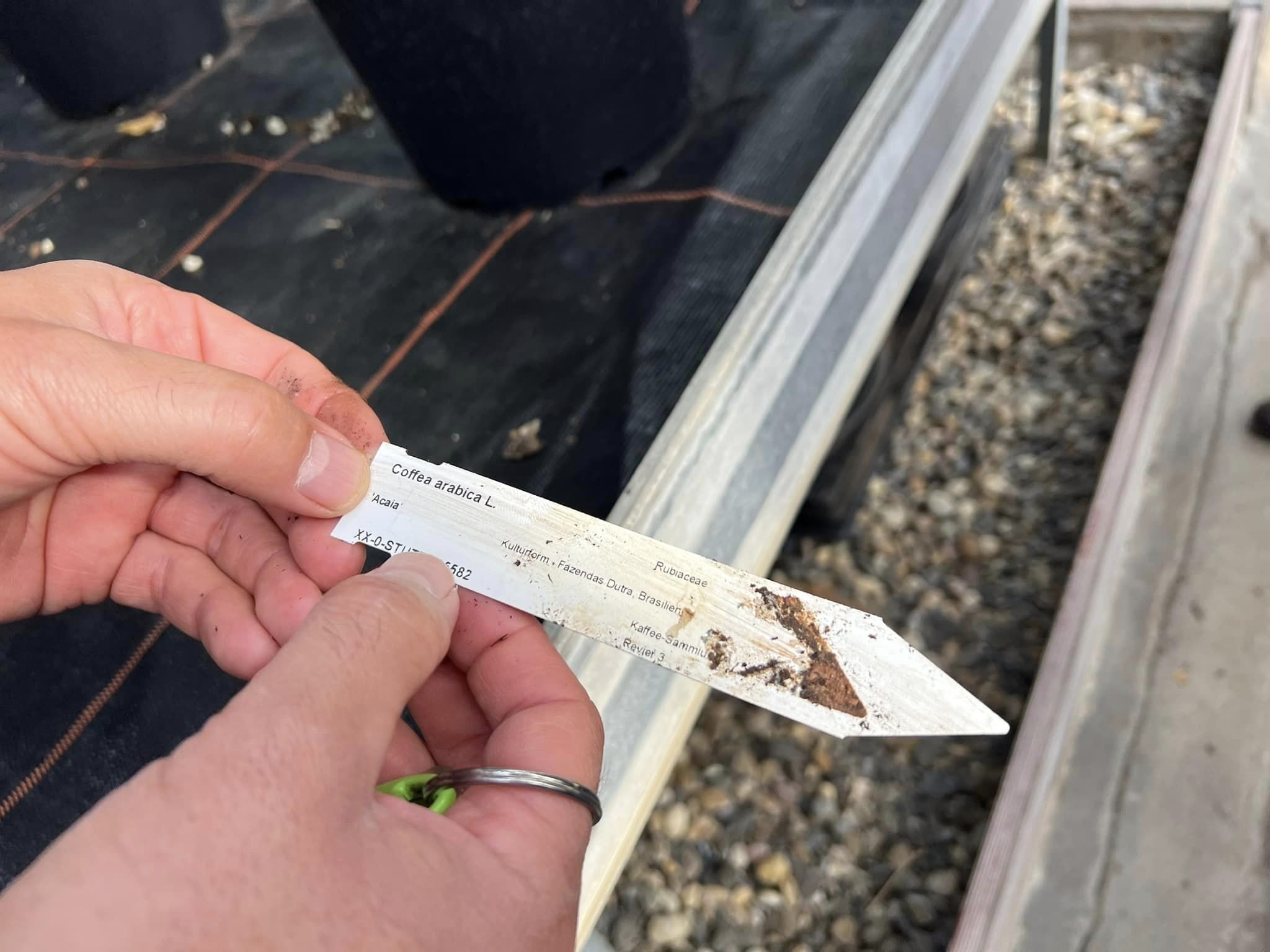

Wilhema Botanical Garden is one of the largest conservation and collection centres for Arabica coffee cultivars globally, currently housing a total of 113 varieties. The head of this coffee conservation project, Dr. Björn Schäfer, was the recipient of the Kaldi Award for green coffee in 2020. Interestingly, it was me who presented the award to him that year, a fortuitous connection.

According to Dr. Schäfer's estimate, there are approximately over 300 known Arabica cultivars. Besides Arabica, they also preserve other coffee species. Those ordinary Liberica seeds I brought earlier have now grown into small trees and are displayed alongside other Liberica variants in a warmer greenhouse, which was a sight to behold.

I remember back in 2018, during one of the "Coffee Farmers Seed Swap" events held here, we had specifically retrieved 9 Arabica cultivars, but after returning them to Kuching, we lost track of them.

This time, after Dr. Björn Schäfer examined the tree species records I brought, particularly the significant differences in petal counts, he proposed an intriguing hypothesis about Liberica's mutation on the island of Borneo due to a "genetic bottleneck." It's a fascinating theory that seems to align with the current status of Liberica in our region.

What does "genetic bottleneck" mean? I'll simplify it as best I can. In the field of botany, there's a common phenomenon where a particular plant variety (varieties) is introduced to a new location, typically through human intervention, especially when it's introduced to a small, isolated island, removed from its mainland counterparts.

Under such circumstances, they tend to undergo successive "inbreeding" without choice.

We often mention "external pressures" and "isolated environments" as conditions for species evolution. The forced inbreeding itself is a form of "internal environmental pressure." Under these conditions, rare genetic mutations are passed and amplified, eventually resulting in new varieties (varieties).

If these new varieties are further selectively cultivated by humans, they become what we call "Cultivars."

In fruit trees, the expression of such variation often involves the occurrence of a few abnormal trees within a group of the same species. The most prominent feature is that petal numbers no longer follow the original rules of the species, and there may also be leaf variations. This observation aligns well with what I've seen in Borneo.

However, there's a challenge with these variations (beneficial for the species but daunting for breeders), they exhibit a noticeable "atavistic phenomenon" or "reversion to ancestral traits." To transform a single plant with this variation into a stable cultivar is a long and intricate process. I won't go into the details here; I'll save that for a future write-up when I have more time.

Among the 113 Arabica varieties preserved here, one is especially noteworthy. According to Dr. Schäfer, this particular variety might be proven to be the first Arabica cultivated by humans. It was cultivated around a monastery near a lake in Tanzania over seven centuries ago. It was brought here for genetic testing recently.

If the test results confirm the legend, the history of Arabica's dissemination will be rewritten.